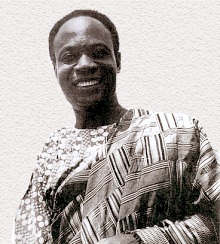

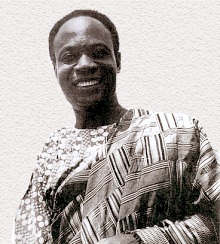

Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972)

Kwame Nkrumah became the first prime and later president of Ghana. He was born on September 21, 1909, at Nkroful in what was then the British-ruled Gold Coast, the son of a goldsmith. Trained as a teacher, he went to the United States in 1935 for advanced studies and continued his schooling in England, where he helped organize the Pan-African Congress in 1945. He returned to Ghana in 1947 and became general secretary of the newly founded United Gold Coast Convention but split from it in 1949 to form the Convention People's party (CPP).

After his 'positive action' campaign created disturbances in 1950, Nkrumah was jailed, but when the CPP swept the 1951 elections, he was freed to form a government, and he led the colony to independence as Ghana in 1957. A firm believer in African liberation, Nkrumah pursued a radical pan-African policy, playing a key role in the formation of the Organization of African Unity in 1963. As head of government, he was less successful however, and as time passed he was accused of forming a dictatorship. In 1964 he formed a one-party state, with himself as president for life, and was accused of actively promoting a cult of his own personality. Overthrown by the military in 1966, with the help of western backing, he spent his last years in exile, dying in Bucharest, Romania, on April 27, 1972. His legacy and dream of a "United States of African" still remains a goal among many.

Nkrumah was the motivating force behind the movement for independence of Ghana, then British West Africa, and its first president when it became independent in 1957. His numerous writings address Africa's political destiny. The following discusses his objectives for Africa and issues for the organization of government there.

Continental Government for Africa

We have seen, in the example of the United States how the dynamic elements within society understood the need for unity and fought their bitter civil war to maintain the political union that was threatened by the reactionary forces. We have also seen, in the example of the Soviet Union, how the forging of continental unity along with the retention of national sovereignty by the federal states, has achieved a dynamism that has lifted a most backward society into a most powerful unit within a remarkably short space of time. From the examples before us, in Europe and the United States of America, it is therefore patent that we in Africa have the resources, present and potential, for creating the kind of society that we are anxious to build. It is calculated that by the end of this century the population of Africa will probably exceed five hundred millions.

Our continent gives us the second largest land stretch in the world. The natural wealth of Africa is estimated to be greater than that of almost any other continent in the world. To draw the most from our existing and potential means for the achievement of abundance and a fine social order, we need to unify our efforts, our resources, our skills and intentions.

At present most of the independent African states are moving in directions, which expose us to the dangers of imperialism and neocolonialism. We therefore need a common political basis for the integration of our policies in economic planning, defense, foreign and diplomatic relations. That basis for political action need not infringe the essential sovereignty of the separate African states. These states would continue to exercise independent authority, except in the fields defined and reserved for common action in the interests of the security and orderly development of the whole continent.

In my view, therefore, a united Africa – that is, the political and economic unification of the African Continent – should seek three objectives.

Firstly, we should have an over-all economic planning on a continental basis. This would increase the industrial and economic power of Africa. So long as we remain balkanized, regionally or territorially, we shall be at the mercy of colonialism and imperialism. The lesson of the South American Republics vis-á-vis the strength and solidarity of the United States of America is there for all to see.

Secondly, we should aim at the establishment of a unified military and defense strategy. I do not see much virtue or wisdom in our separate efforts to build up or maintain vast military forces for self-defense which, in any case, would be ineffective in any major attack upon our separate states. If we examine this problem realistically, we should be able to ask ourselves this pertinent question: which single state in Africa today can protect its sovereignty against an imperialist aggressor?

The third objective which we should have in Africa stems from the first two which I have just described . . . a unified foreign policy and diplomacy to give political direction to our joint efforts for the protection and economic development of our continent . . . The desirability of a common foreign policy which will enable us to speak with one voice in the councils of the world, is so obvious, vital and imperative that comment is hardly necessary.

I am confident that it should be possible to devise a constitutional structure applicable to our special conditions in Africa and not necessarily framed in terms of the existing constitutions of Europe, America or elsewhere, which will enable us to secure the objectives I have defined and yet preserve to some extent the sovereignty of each state within a Union of African states.

We might erect for the time being a constitutional form that could start with those states willing to create a nucleus, and leave the door open for the attachment of others as they desire to join or reach the freedom which would allow them to do so. The form could be made amenable to adjustment and amendment at any time the consensus of opinion is for it. It may be that concrete expression can be given to our present ideas within a continental parliament that would provide a lower and an upper house, the one to permit the discussion of the many problems facing Africa by a representation based on population; the other, ensuring the equality of the associated states, regardless of size and population, by a similar, limited representation from each of them, to formulate a common policy in all matters affecting the security, defense and development of Africa. It might, through a committee selected for the purpose, examine likely solutions to the problems of union and draft a more conclusive form of constitution that will be acceptable to all the independent states.

The survival of free Africa, the extending independence of this continent, and the development towards that bright future on which our hopes and endeavors are pinned, depend upon political unity.

Under a major political union of Africa there could emerge a United Africa, great and powerful, in which the territorial boudoirs which are the relics of colonialism will become obsolete and superfluous, working for the complete and total mobilization of the economic planning organization under a unified political direction. The forces that unite us are far greater than the difficulties that divide us at present, and our goal must be the establishment of Africa's dignity, progress and prosperity.

Kwame Nkrumah's contribution to the decolonization process in Africa

September 16, 04: by Leslie

BUY THESE BOOKS

Education 2000 Raceandhistory.com

|