Tribal Africans in India: A history of alienation

The author is an environmental activist with

Kalpavriksh, Pune.

The history of the Andaman and Nicobar islands is

today a conveniently comfortable one: of the British

and "Kalapani"; of World War I and the Japanese

occupation, of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Veer

Savarkar, the first hosting of the Indian National Flag

and of modern mini India where all communities and

religions live in peace and harmony. But like all histories, this one too, is incomplete.

The history of the Andaman and Nicobar islands is

today a conveniently comfortable one: of the British

and "Kalapani"; of World War I and the Japanese

occupation, of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Veer

Savarkar, the first hosting of the Indian National Flag

and of modern mini India where all communities and

religions live in peace and harmony. But like all histories, this one too, is incomplete.

It is the story of the victors, of the

people who have today come to dominate these islands.

The vanquished as they say, have no tales to tell. The

history of these islands as we tell it, as we are told

it is, is silent in many parts. There are gaping holes

that are conveniently allowed to remain so.

This history says nothing of the past, the

present and the future of those people and communities

that originally belong to the islands. For that matter,

the islands belong to them, but ironically the people

who write the history are we, the modern democratic

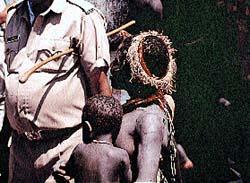

Indian state. The people in question are the ancient

tribal communities that live here, particularly the

negrito group of the Andaman islands - the Great

Andamanese, the Onge, the Jarawa and the Sentinelese.

These are communities that have lived and flourished

here for at least 20,000 years, but the end could well

be round the corner. Just a 150 years ago the

population of the tribal communities was estimated to

be at least 5,000. Today however, while the total

population of the Andaman and Nicobar islands has risen

to about four lakhs, the population of all these four

communities put together is not more than a mere 500.

These communities of thousands of individuals

with a living lineage going back to 20,000 years have

been brought to this sorry state in a mere 150 years.

It definitely began with the British and their

policies. And was continued with clinical efficiency

(sic) by modern independent India.

Independent India was only about a couple of

decades old, a young thriving democracy as would have

been called then. But this vibrant democracy was then

already set on course to becoming a coloniser itself.

From colony of the British to coloniser of the Andaman

islands (and many other places too), the step for India

was an amazingly easy one, almost, it would seem, a

natural one! In the late Sixties an official plan of

the Government of India to "colonise" (and this was the

term used) the Andaman and Nicobar islands was firmly

in place.

The forests were "wastelands" that needed to be

tamed, settled and developed. It did not matter that

these forests were the home of a myriad plants and

animals that had evolved over aeons. It did not matter

that ancient tribal peoples were already living here

for centuries, neither that they were physically and

spiritually sustained by these forests. The idea that

forests could mean more than just the timber the trees

provided had not even taken seed in the national

consciousness. The Nehruvian dream of massive

industrialisation was still calling and the rich

evergreen forests of the islands promised abundant

timber to fuel it. The tribals, too, had to be

civilised; brought into the Indian mainstream. There

was no question of trying to understand, forget about

asking what was it that the Onge, the Andamanese or the

Jarawa wanted themselves.

Tribal cultures the world over are intricately

linked with the forests they live in. The story or

should we call it the "history" of modern civilisation

is largely one of the taming and the destruction of the

great forests of the world and the innumerable tribal

communities that lived therein. The Andaman islands is

a good example. By various means, both intended and

unintended, the tribal communities have been constantly

alienated from their forests, their lands and their

very cosmos that is built around all these. One of the

subtle but classic examples is the Hinduisation of the

name Andaman itself and the attempt to pass it off as

the only truth. The standard and universal answer to

the question of its origin is the well known Hindu god

Hanuman. That the state too conveniently believes this

is evident from the fact this is the story that goes

out in the sound and light show that plays every

evening at the Cellular Jail in Port Blair. No one is

bothered that there are many other explanations why the

Andamans is called so. Researches On Ptolemy's

Geography Of Eastern Asia," a book written by Colonel

GF Gerini in 1909 makes incredible reading in this

context, but obviously not many have bothered to read

it. It is hardly surprising then that we care even less

to know what the tribals call these islands.

The repercussions of this dominant mindset is all

too evident when one looks at what is happening to the

forests and the tribal communities. The Great

Andamanese have been wiped out as viable community.

This community which had an estimated 3,000 members

about a 150 years ago, is today left with only about

30. The Onges of the island of Little Andaman (they

call it Egu-belong) today number only 100. The 1901

census estimated it to be 601. Till a couple of years

ago the Jarawa were extremely hostile to the outside

world. This hostility and self-maintained isolation in

the impenetrable rainforests of these islands had

ensured that their community, culture and forest home

remained intact and unharmed. It was however, never our

intention to let them be. The Andaman Trunk Road was

constructed through the heart of the very forests the

Jarawa call home. It destroyed precious forests and

bought in various developments that are proving to be

disastrous for the Jarawa. As a result of a combination

of such factors, most not known or understood, the

Jarawas recently shed their hostility and have begun to

come out from their forests "voluntarily." It could

well be the first step on the route that the Great

Andamanese and the Onge were forced to take many

decades ago. Annhilation! A huge epidemic of measles

recently affected the Jarawa and a number of them are

undergoing treatment for tuberculosis.

The lessons of history have not been learnt. May

be they are being deliberately ignored. It could well

be worth our while to get these tribals out of our way.

Only then can the precious tropical hardwoods that

stand in their forests and the very lands that these

forests stand be put to "productive" use. Little

Andaman is a classic case. Thousands of settlers from

mainland India were brought and settled here and the

forests were opened up for logging in the early

Seventies as part of the "colonisation" plan. An Onge

tribal reserve was created, but for more than a decade

now this reserve has been violated for timber

extraction. The attitude of the settlers who today live

on the land that belongs to the Onge only reflects that

of the powers that be. They ridicule the tribals as

uncivilised junglees. Vices like alcoholism were

introduced; the addiction is now used by the settlers

to exploit the resources from the forests. Poaching and

encroachment inside the Onge reserve too, are ever on

the increase.

In the early Sixties, the Onge were the sole

inhabitants of Little Andaman (Egu belong). Today, for

each Onge, there are at least 120 outsiders here and

this imbalance is rapidly increasing. What more needs

to be said?

____________________________________

Copyrights © 2000, The Hindu.

For fair use only

Homepage / Historical Views

^^ Back to top

|

The history of the Andaman and Nicobar islands is today a conveniently comfortable one: of the British and "Kalapani"; of World War I and the Japanese occupation, of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Veer Savarkar, the first hosting of the Indian National Flag and of modern mini India where all communities and religions live in peace and harmony. But like all histories, this one too, is incomplete.